BY Xiao Quan

Of course, such techniques are not original. Experiments with sound, voice and presence define much of contemporary and avant-garde poetics. As to how I would blend all of these voices into a melting pot, I, too, don’t quite know. I just do so with a little common sense, and let the technique function as it best can.

Do you see a poem as an experience or as an act?

One can’t be separated from the other. “Poetry is experience” — this is a universally-known dictum from the German poet, Rilke. Even Nabokov who detested Rilke, also said, “Poetry is a distant past.” But poetry must also be an act — in a modern sense, and even more so in a post-modern context. If I must choose between the two of them, an old poet like me would go for the former.

Ezra Pound says, “Make it new.” You have a skillful way of making the language both “new” and “fresh” when it comes to developing a unique signature in Chinese in terms of the language as a tradition, but without the antecedents of a so-called “modern” poetry or the preconceived “traditional.” In “A Year of Chronicles in Suzhou” and “In Qing Dynasty,” for instance, the ancient idioms ( 成语 ), proverbs ( 俗语 ) and sayings ( 惯用语 ) are able to express intention: they speak and show without telling.

My understanding and approach toward tradition draws its influence from the celebrated essay of T.S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Personally, I don’t have any new perspective or unusual rhetoric to offer regarding “tradition.” To put it more plainly, reading Chinese classical poetry, for a contemporary reader, is to foster one’s qi. It is a way of literary self-cultivation through reading choices and learning of oneself.

So how do/should we read them? Obviously I am thinking of Eliot’s famous saying, “Immature poets imitate, great poets steal.” Or as Vladimir Nabokov once said, “Only true geniuses will take things from others to use as their own.” Work that can be stolen or “taken to be used” is never first-rate work. However, these less than first-rate writings are able to survive (survival being their best fate) because they are waiting to be read by a certain great poet, to be taken away again.

To take a step further, many writings by second-rate poets or soon-to-be-first-rate poets are often destined to be “stolen” by another strong poet. The former exists only for the latter. After which, the former “dies,” for its mission is over. Does that mean that a great poet would steal everywhere? No. Certainly there are limits. As I have previously mentioned, great poets will only steal from second-rate or soon-to-be-first-rate poets. If they meet another true poet, no matter how they would like to steal, they cannot. Even if they can, it is useless. They will end up as mere imitators. Let me also quote another thought-provoking saying, “Learn from the living Eileen Chang, and the dead Hu Lancheng.” (“学张爱玲生,学胡兰成死”) As a representative figure of the post-“Misty” poets, what are your thoughts about the tides of poetry and artistic search in the present-day China?

When a tide is over, one will become a tradition. When one becomes a tradition, he or she will also open up a new tide. This dialectic simply means: the more you pursue the art that impassions you, the more you will find yourself right at the source of a tide.

As a contemporary Chinese poet, to what extent does the question or issue of a readership stand as an agenda for you?

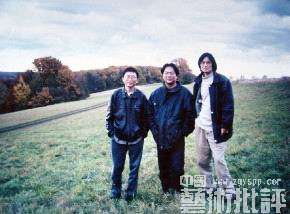

Bai Hua (left) with his friends Zhang Zao

and Zhang Qikai near the Black Forest

in Tübingen, Germany, November 1997

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE POET

Of course, the more readers there are, the better it is. We can sell more poetry books. But the fate of contemporary poetry has already determined its very small scope of readership. Contemporary poetry is aimed at those who suffer or are ill in their inner lives. Let me make a bold guess: these are — very possibly — men who are overly feminine and women who are overly masculine.

Do you have an ideal reader?

By chance you may meet this reader, but he or she cannot be sought. If you allow a most honest answer from me: my ideal reader can only be myself. So, to reveal something that is not quite proper in terms of public relations: I usually only read my poems. In fact, I read all of them again and again, to the extent that I almost do not read others’ work.

How do you nourish your poetic life?

Read, read, read. Non-stop. In a jumble, in chaos.

Being such a voracious reader, do you also see other “non-literary” possibilities as your artistic influences? If so, what are they?

I have never really thought about this, but now that you mention it, I did think about an influence that is not literary-related — music. Often, I finish some of my poems while listening to a melody or while singing. Some simple and lyrical music as long as it can stimulate my thoughts. Sometimes films excite me, too. For example, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Mirror (1975) had directly inspired me to write a stanza in my poem, “Gift”:

In the heavy rain, she opened the iron door of the press

rushing into the layout room of socialism, verifying

an original phrase from Chekhov’s Collected Works. Perhaps

sparrows fly by the window dotted with rust stains

— Edited and adapted by the translator with Sally Molini, this is an abridged version of an interview

originally conducted in Chinese, which also appeared in the literary magazine Chutzpah

川公网安备 51041102000034号

川公网安备 51041102000034号