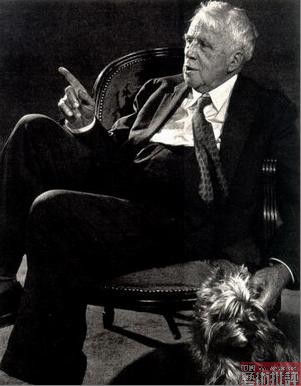

Robert Frost(1874-1963),20世纪美国最杰出的诗人,作品以朴素、深邃著称,庞德、艾略特、博尔赫斯、布罗茨基等大师都对之有过相当的评价。他的一生,既不幸又充满光彩:有40岁之前的坎坷曲折,后半生的寂寞孤独,又有四获普利策诗歌奖、44种名誉学位和种种荣誉。他常常被称作美国诗坛的两面神,作品和人格遭到攻击,却又始终维持一个大诗人的和蔼形象,又是诗人、农夫和哲学家的三位一体。弗罗斯特一直通过具体的实物、情景写诗,斯蒂文斯说,你爱写实物,弗罗斯特反唇相讥,你爱写古董,这其实是诗人预先选择的精神图式和写作形式,一生几乎没有多大变化。作为以自然方式关注现实的大诗人,他对世界的态度既不像华兹华斯那样充满柔情,也不像斯蒂文斯那样粗壮、强硬,而是显得矛盾、折中,和他的精神导师爱默生一样带有超验主义。他向维吉尔学写田园牧歌,向哈代、叶芝等人学习平淡而富有暗示的语言,但用意更精深,作品常常通过时空反差的形式,也就是具体情境中的变化、对比,从而形成一个个坚固封闭却又极其开放的诗歌文本,简洁地表达出存在的真相,化腐朽为神奇。他喜欢戴着面具写作,崇尚文学的游戏原则,一开始就写得朴素含蓄,第一本诗集《男孩的意愿》(1913)就显示了过人的语言才华。虽然弗罗斯特一直戴着面具写作,但我更愿意将他称为 “一位伟大的徘徊者”。他徘徊在自然和人类、自我和事物、现实和理想之间,像被上帝驱逐的天使一样平静而又苦恼地审视着尘世生活。弗罗斯特幼年丧父,中年丧妻,老年丧子,他的坎坷人生常使他在作品中流露阴暗和悲观,但他更多是想用诗歌这种崇高的艺术形式排遣存在的焦虑和慌乱。他明智而不极端,曾在一首诗中将世界比作自己的情人,于是喋喋不休的吵闹就成为他摇曳的情思和毕生的哲学追求。他非常懂得独特是什么东西。他对现代诗歌的贡献,主要在于果断地拒绝了自由诗体(free verse)的潮流,以个人的兴趣探索出结合传统的抑扬格韵律和日常生活话语、结合古典人文情怀和现代怀疑精神的新诗体 (blank verse),看似保守,实则妙笔生花。在精神的高标和题材的深广度上,自波德莱尔以来的诗歌大师几乎无一人能和但丁相比,但弗罗斯特的探索应该说是走得最自然、最深远的,所以深受世界各国各层次读者的欢迎,在美国更是家喻户晓。弗罗斯特创作的朴素无华、寓意深刻的抒情短诗和戏剧性浓烈、艺术性高超的叙事长诗应该说经得起任何考验,无韵诗、变体十四行、双行体等各种形式的作品都有佳作,和华兹华斯一样堪称体裁大师。他自16岁写诗,一直到89岁去世,半个多世纪笔耕不辍,共出版10余本诗集,主要有《波士顿以北》(1914),《山间》(1916),《新罕布什尔》(1923),《西流的小溪》(1928),《见证树》(1942),《林间空地》(1962)等,在美国文学史上具有独特的地位,在世界文学史上也是一颗璀璨之星。然而,弗罗斯特在中国,如同余光中所说“损失惨重”,因为日常语言性的诗歌经过翻译,精华丧失殆尽。这里选译的几十首诗,表面上是弗罗斯特各个时期的创作精华,却也极有可能仍是以讹传讹。但是,通过它们,我们大致可以感受一位天才诗人的精神世界,一种对人类、对尘世生活的个性理解。它们对于中国当代诗人的写作,应该说依然具有非常重要的借鉴意义。

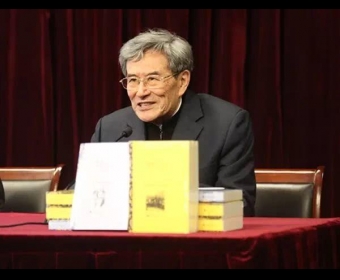

译者小传

徐淳刚(1975- ),蓝田猿人后裔。著有诗集、小说、哲学随笔。现居西安。

西去的溪水

□ 山

山,像是暗中紧握着小镇。

有一次,临睡前,我望了很长时间的山:

我注意到,它黑沉沉的身躯戳上了天,

使我看不到西天上的星。

它,似乎离我很近:就像

我身后的一面墙,在风中庇护着我。

拂晓前,当我为了看个新鲜而向前走,

我发现山和小镇之间,

有田野,一条河,以及对岸,大片的田野。

那时,正是枯水期,河水

漫过鹅卵石哗哗地流去,

但从它流的样子,仍可想见春天的泛滥;

一片漂亮的草地在河谷中闪现,草里

有沙子,和被剥去皮的浮木。

我穿过河流,转悠着走向山。

在那里,我遇见了一个面色苍白的男人

他的牛拉着沉重的车子缓慢地走着,

就是拦住他,让他停下来也没关系。

“这是什么镇?”我问。

“这儿?卢恩堡。”

看来,是我搞错了:我逗留的小镇,

在桥那边,不属于山,

晚上我感觉到的,只是它朦胧的影子。

“你的镇子在哪儿?是不是很远?”

“这边没有镇,只有零星几个农场。

上次选举,我们才六十个人投票。

我们的人数,总不能自然而然地多起来:

那家伙,把地方占完了!”他扬了扬手中的小棍

指着挺立在那边的山。

山腰的牧场,向上延伸了一小段,

然后是前面有一排树木的墙:

再往上,就只能看见树梢,悬崖峭壁

在树叶中间若隐若现。

一条干涸的溪谷在大树枝下

一直伸进牧场里。

“那看上去像条路。

是不是从这儿能上到山顶?——

今天早上不行,只能换个时间:

我现在该回去吃饭了。”

“我不建议你从这儿上山。

没有什么正路,那些

上过山的,都是从拉德家那儿往上爬的。

得往回走十五里。你可不能走错了:

他们在去年冬天把远处的一些树砍掉了。

我倒是想捎你去,可惜不顺路。”

“你,从来没爬过它?”

“我以前上到过山腰

打过鹿,钓过鱼。有条小溪

的源头就在那儿的什么位置——我听说

在正顶端,最高处——真是怪事。

不过,这小溪会让你感兴趣,

因为,它在夏天总是冷的,冬天却暖。

就说冬天,那水雾好比

公牛在喘气,壮观得太,

水汽沿着两岸的灌木丛蔓延,使它们长了

一寸多厚的针状霜毛——

那样子你知道。然后就是,阳光在上面闪闪发亮!”

“这倒是天下一景

从这座山上望去——如果一直到山顶

没有那么多树就好了。”我透过浓密的树叶

看见阳光和树影中大片的花岗岩台阶,

心想,爬山时膝盖会碰在那上面

身后,还有十几丈的悬崖深渊;

转过身子,坐在上面向下俯视,

胳膊肘就会碰到岩缝里长出的羊齿草。

“这我不敢说。但泉水有,

正好在山顶,几乎像一个喷泉。

应该值得去看一看。”

“或许,它真的在那儿。

你,从来没看到过?”

“我想,它在那儿这个

事儿不值得怀疑,虽说我从来没见过。

它或许不是在正顶端:

山间的水源,不一定非得从

最高处那么长一路下来,

从大老远爬上来的人或许不会注意

其实,头顶上还有很远。

有一次,我对一个爬山的人说

你去看看,再告诉我它到底是什么样子。”

“他说了什么?”

“他说,在爱尔兰

的什么地方,山顶上有个湖。”

“湖是另一回事。泉水呢?”

“他爬得不够高,没看见。

所以我才不建议你从这边爬——

他就是从这儿爬的。我总想上去

亲眼看看,但是你知道:

一个人在这山里呆了一辈子

爬山就没有意思。

我爬它干什么?要我穿上工作服,

拿着根大棒子,去赶在挤奶时间

吃草还没回来的奶牛?

或者,提把猎枪,去对付迷路的黑熊?

反正,不能只为爬上去而爬。”

“我不想爬,也不会爬——

不为上山。那山,叫什么?”

“我们都叫它霍尔,不知道对不对。”

“能不能绕着它走?会不会太远?”

“你可以开车转转,但要在卢恩堡境内,

不过,你能做的也就是这些,

因为卢恩堡的边界线紧紧贴着山脚。

霍尔就是镇区,镇区就是霍尔——

一些房屋星星点点散布在山脚下,

就像是悬崖上崩裂的圆石头,

朝远处多滚了一截子。”

“你刚才说,泉水冬天暖、夏天冷?”

“我根本不认为,水有什么变化。

你和我都清楚,说它暖

是跟冷比,说它冷,是跟暖比。

真有意思,同一件事,就看你怎么说。”

“你一辈子都在这儿住?”

“自从霍尔

的大小还不如一个——”说的什么,我没听见。

他用细长的棍子轻轻碰了碰牛鼻子

和后面的肋骨,把绳子朝自己拽了拽,

吆喝几声,然后慢悠悠地走远了。

The Mountain

The mountain held the town as in a shadow

I saw so much before I slept there once:

I noticed that I missed stars in the west,

Where its black body cut into the sky.

Near me it seemed: I felt it like a wall

Behind which I was sheltered from a wind.

And yet between the town and it I found,

When I walked forth at dawn to see new things,

Were fields, a river, and beyond, more fields.

The river at the time was fallen away,

And made a widespread brawl on cobble-stones;

But the signs showed what it had done in spring;

Good grass-land gullied out, and in the grass

Ridges of sand, and driftwood stripped of bark.

I crossed the river and swung round the mountain.

And there I met a man who moved so slow

With white-faced oxen in a heavy cart,

It seemed no hand to stop him altogether.

“What town is this?” I asked.

“This? Lunenburg.”

Then I was wrong: the town of my sojourn,

Beyond the bridge, was not that of the mountain,

But only felt at night its shadowy presence.

“Where is your village? Very far from here?”

“There is no village--only scattered farms.

We were but sixty voters last election.

We can"t in nature grow to many more:

That thing takes all the room!”He moved his goad.

The mountain stood there to be pointed at.

Pasture ran up the side a little way,

And then there was a wall of trees with trunks:

After that only tops of trees, and cliffs

Imperfectly concealed among the leaves.

A dry ravine emerged from under boughs

Into the pasture.

“That looks like a path.

Is that the way to reach the top from here?--

Not for this morning, but some other time:

I must be getting back to breakfast now.”

“I don"t advise your trying from this side.

There is no proper path, but those that have

Been up, I understand, have climbed from Ladd"s.

That"s five miles back. You can"t mistake the place:

They logged it there last winter some way up.

I"d take you, but I"m bound the other way.”

“You"ve never climbed it?”

“I"ve been on the sides

Deer-hunting and trout-fishing. There"s a brook

That starts up on it somewhere--I"ve heard say

Right on the top, tip-top--a curious thing.

But what would interest you about the brook,

It"s always cold in summer, warm in winter.

One of the great sights going is to see

It steam in winter like an ox"s breath,

Until the bushes all along its banks

Are inch-deep with the frosty spines and bristles--

You know the kind. Then let the sun shine on it!”

“There ought to be a view around the world

From such a mountain--if it isn"t wooded

Clear to the top.”I saw through leafy screens

Great granite terraces in sun and shadow,

Shelves one could rest a knee on getting up--

With depths behind him sheer a hundred feet;

Or turn and sit on and look out and down,

With little ferns in crevices at his elbow.

“As to that I can"t say. But there"s the spring,

Right on the summit, almost like a fountain.

That ought to be worth seeing.”

“If it"s there.

You never saw it?”

“I guess there"s no doubt

About its being there. I never saw it.

It may not be right on the very top:

It wouldn"t have to be a long way down

To have some head of water from above,

And a good distance down might not be noticed

By anyone who"d come a long way up.

One time I asked a fellow climbing it

To look and tell me later how it was.”

“What did he say?”

“He said there was a lake

Somewhere in Ireland on a mountain top.”

“But a lake"s different. What about the spring?”

“He never got up high enough to see.

That"s why I don"t advise your trying this side.

He tried this side. I"ve always meant to go

And look myself, but you know how it is:

It doesn"t seem so much to climb a mountain

You"ve worked around the foot of all your life.

What would I do? Go in my overalls,

With a big stick, the same as when the cows

Haven"t come down to the bars at milking time?

Or with a shotgun for a stray black bear?

Twouldn"t seem real to climb for climbing it.”

“I shouldn"t climb it if I didn"t want to--

Not for the sake of climbing. What"s its name?”

“We call it Hor: I don"t know if that"s right.”

“Can one walk around it? Would it be too far?”

“You can drive round and keep in Lunenburg,

But it"s as much as ever you can do,

The boundary lines keep in so close to it.

Hor is the township, and the township"s Hor--

And a few houses sprinkled round the foot,

Like boulders broken off the upper cliff,

Rolled out a little farther than the rest.”

“Warm in December, cold in June, you say?”

“I don"t suppose the water"s changed at all.

You and I know enough to know it"s warm

Compared with cold, and cold compared with warm.

But all the fun"s in how you say a thing.”

“You"ve lived here all your life?”

“Ever since Hor

Was no bigger than a----”What, I did not hear.

He drew the oxen toward him with light touches

Of his slim goad on nose and offside flank,

Gave them their marching orders and was moving.

□ 蓝莓

“你应该见过,我在去村子的路上

看到的,就在我今天穿过莫德森牧场:

蓝莓像你的大拇指一样大,

真正的天蓝色,沉甸甸的,像是等着

掉进第一个来这儿的桶里去打鼓!

全都熟了,并不是有的青绿

有的成熟!你应该看见过!”

“我不知道,你说的是牧场的哪块儿。”

“你知道,他们在那儿砍过树——让我想想——

是两年前——好像不对——或者

比这还要晚?——反正,接下来是秋天

大火蔓延,把那里烧得只剩下墙壁。”

“不对吧?那里还没长出灌木什么的。

尽管那条路,总会长满蓝莓:

现在,在松树下的任何地方,还看不到

它们的一点点儿影子,

要是,没有松树的话,你就是把

整个牧场都烧光,哪怕不剩一片羊齿草

或者蒿子,更别说一根树枝,

可是很快,那些莓子就会长出来

像魔术师的把戏一样,让人难以理解。”

“它们,一定是用炭灰给自己上肥呢。

有时,我在那儿就闻到了煤烟味儿。

毕竟,它们真是给黑檀树笼罩着:

那种蓝,好像是风吹来的薄雾,

但是,如果你用手一碰,它就变得黯淡了,

还不如制革的人采的那种棕褐色。”

“莫德森知道他有这些莓子吗,你想?”

“可能吧,但他不会在意,他不会

离开,丢下他的红眼小鸟不管。

当然,他不会弄出个什么理由

不让别人去他那里——他就是这种人。”

“我想,你在那儿没见到劳恩吧。”

“不,我正好见到他了。你不知道,

我正要穿过那片蓝莓

再绕过围墙,走上大路时,

就见他赶着马车经过,

拉着他那叽叽喳喳的一家子,

但是劳恩,这个当爸的,他停下是为拾掇车。”

“他看见你了?然后,怎么样?他不高兴?”

“他,只是对我连连点头。

你知道,他经过时总这么客气。

但是,他显然在想一件重要的事,

——我从他的眼里能看出来——:

‘我的莓子还在那儿呢,我猜它们

已经熟透了。唉,我该为这事感到惭愧。’”

“他这个人,比我能叫上名字的人都要勤俭。”

“或许,他真的勤俭;这也应该,

不是有那么多张小嘴等着他喂呢嘛。

人家说,他喂给孩子的都是野莓子,

喂鸟似的。他家在别处还储存了不少。

他们常年都吃这个,吃不了的

他就放到商店里卖掉,给娃买鞋穿。”

“谁会在意别人说什么?这样挺好,

只得到老天爷愿意赏赐的,

而没逼着他去耙地、犁地。”

“我希望,你改天瞧瞧他那么深地哈腰——

还有那些小家伙的脸。他们没一个回头,

看上去既严肃又荒谬。”

“我要是知道,他们知道的一半就好了,

就是,所有的莓子和其它的果子在哪里,

或许,酸果蔓长在沼泽里,悬钩子则在

满是鹅卵石的山顶上,想摘就去摘。

有一天,我碰到他们,他们每个人都把花

插在像阵雨一样新鲜的莓子里;

一些奇怪的种类——他们说这东西没名字。”

“我给你说过,我们来这儿不久,

我几乎使劳恩这个穷鬼变得乐观起来。

就说那次吧,我一个人去他那儿,

问他,知不知道有什么野莓子

可以摘。这狗日的,他说,如果他知道

倒是很乐意说出来,但是年景不好。

有个地方长过一些——现在,全不见了。

他就是不说它们长在哪儿。他还说:

‘我保证——我保证’——尽量客气,好让我信。

他对站在门里的妻子说,‘让我想想,

娃他妈,我们不知道哪里有莓子,对不对?’

这就是他那张坦率的脸所说出的全部。”

“如果,他认为所有的莓子都是为他长的,

那他就错了。要是有兴致,

今年,我们就到莫德森家的牧场那儿去摘。

我们早上去,就是说,如果天气好,

阳光暖暖地照着,那蔓一定还是湿的。

已经好长时间没摘莓子,我几乎忘了

我们以前是咋样摘莓子的:我们总是

四处看看,然后像轮流唱歌一样隐现,

谁也看不见谁,也听不到声,

除非当你说,我把一只鸟

吓得飞离了窝,我就说,那是你干的。

‘好,反正是我们中的一个。’像是在抱怨

那只鸟绕着我们打转。然后

我们摘了一会儿莓子,直到我担心你走远了

甚至把你弄丢了。因为距离远

我大声喊着你,声音传了出去,

但你答应的时候,声音却很低

就像在说话——你在我旁边站起身来,记得不?”

“也许,我们在那儿找不到乐趣——

不太可能,因为劳恩的孩子都要去。

他们明天就去,甚至今天晚上。

他们不会对我们客气——也说不定——

因为,在他们眼里,别人没有权力

去他们采莓子的那块儿。但是,我们不管这些。

你应该见过,莓子在雨中是什么样子,

在层层枝叶中间,蓝莓和水珠混在一起,

就像两种珍宝,像小偷一眼瞅见的。”

译注:

1、蓝 莓:学名越橘,果实为浆果,呈蓝色,近圆形,营养丰富,原产和主产于美国。

2、羊齿草:学名蕨类,古生代植物(后代大多已经灭绝),《诗经:召南·草虫》有“言采其蕨”,古代也叫蕨萁、月尔等。

3、悬钩子:《尔雅》中称木莓、山莓,果实为浆果,圆锥形或球形,可入药。

Blueberries

“You ought to have seen what I saw on my way

To the village, through Mortenson"s pasture to-day:

Blueberries as big as the end of your thumb,

Real sky-blue, and heavy, and ready to drum

In the cavernous pail of the first one to come!

And all ripe together, not some of them green

And some of them ripe! You ought to have seen!”

“I don"t know what part of the pasture you mean.”

“You know where they cut off the woods--let me see--

It was two years ago--or no!--can it be

No longer than that?--and the following fall

The fire ran and burned it all up but the wall.”

“Why, there hasn"t been time for the bushes to grow.

That"s always the way with the blueberries, though:

There may not have been the ghost of a sign

Of them anywhere under the shade of the pine,

But get the pine out of the way, you may burn

The pasture all over until not a fern

Or grass-blade is left, not to mention a stick,

And presto, they"re up all around you as thick

And hard to explain as a conjuror"s trick.”

“It must be on charcoal they fatten their fruit.

I taste in them sometimes the flavour of soot.

And after all really they"re ebony skinned:

The blue"s but a mist from the breath of the wind,

A tarnish that goes at a touch of the hand,

And less than the tan with which pickers are tanned.”

“Does Mortenson know what he has, do you think?”

“He may and not care and so leave the chewink

To gather them for him--you know what he is.

He won"t make the fact that they"re rightfully his

An excuse for keeping us other folk out.”

“I wonder you didn"t see Loren about.”

“The best of it was that I did. Do you know,

I was just getting through what the field had to show

And over the wall and into the road,

When who should come by, with a democrat-load

Of all the young chattering Lorens alive,

But Loren, the fatherly, out for a drive.”

“He saw you, then? What did he do? Did he frown?”

“He just kept nodding his head up and down.

You know how politely he always goes by.

But he thought a big thought--I could tell by his eye--

Which being expressed, might be this in effect:

‘I have left those there berries, I shrewdly suspect,

To ripen too long. I am greatly to blame. ’”

“He"s a thriftier person than some I could name.”

“He seems to be thrifty; and hasn"t he need,

With the mouths of all those young Lorens to feed?

He has brought them all up on wild berries, they say,

Like birds. They store a great many away.

They eat them the year round, and those they don"t eat

They sell in the store and buy shoes for their feet.”

“Who cares what they say? It"s a nice way to live,

Just taking what Nature is willing to give,

Not forcing her hand with harrow and plow.”

“I wish you had seen his perpetual bow--

And the air of the youngsters! Not one of them turned,

And they looked so solemn-absurdly concerned.”

“I wish I knew half what the flock of them know

Of where all the berries and other things grow,

Cranberries in bogs and raspberries on top

Of the boulder-strewn mountain, and when they will crop.

I met them one day and each had a flower

Stuck into his berries as fresh as a shower;

Some strange kind--they told me it hadn"t a name.”

“I"ve told you how once not long after we came,

I almost provoked poor Loren to mirth

By going to him of all people on earth

To ask if he knew any fruit to be had

For the picking. The rascal, he said he"d be glad

To tell if he knew. But the year had been bad.

There had been some berries--but those were all gone.

He didn"t say where they had been. He went on:

"I"m sure--I"m sure"--as polite as could be.

He spoke to his wife in the door, ‘Let me see,

Mame, we don"t know any good berrying place? ’

It was all he could do to keep a straight face. ”

“If he thinks all the fruit that grows wild is for him,

He"ll find he"s mistaken. See here, for a whim,

We"ll pick in the Mortensons" pasture this year.

We"ll go in the morning, that is, if it"s clear,

And the sun shines out warm: the vines must be wet.

It"s so long since I picked I almost forget

How we used to pick berries: we took one look round,

Then sank out of sight like trolls underground,

And saw nothing more of each other, or heard,

Unless when you said I was keeping a bird

Away from its nest, and I said it was you.

"Well, one of us is." For complaining it flew

Around and around us. And then for a while

We picked, till I feared you had wandered a mile,

And I thought I had lost you. I lifted a shout

Too loud for the distance you were, it turned out,

For when you made answer, your voice was as low

As talking--you stood up beside me, you know.”

“We sha"n"t have the place to ourselves to enjoy--

Not likely, when all the young Lorens deploy.

They"ll be there to-morrow, or even to-night.

They won"t be too friendly--they may be polite--

To people they look on as having no right

To pick where they"re picking. But we won"t complain.

You ought to have seen how it looked in the rain,

The fruit mixed with water in layers of leaves,

Like two kinds of jewels, a vision for thieves.”

□ 野葡萄

从什么树上摘不到无花果?

难道葡萄不能从桦树上采摘?

你对葡萄、桦树也就知道这么多。

作为某个秋天,一个把自己挂在

葡萄中间却从桦树上下来的女孩,

我当然知道葡萄长在什么树上。

我来到世上,和任何人没什么两样,

然后长成个有点像男孩的女孩

所以我哥哥不能老把我留在家。

但是,我挂在葡萄中间晃荡的身世

早已因那突如其来的恐慌而消散,

而且就如欧里娣克被找到那样

终于从半空平平安安地回到地面;

那么,我这条命就是凭空捡来的,

我喜欢谁就可以为谁白白浪费掉。

因此,如果你看到我一年过两个生日,

并且以为自己有两个不同的年龄,

那么其中一个比实际的我要小五岁——

一天,我哥哥带我到一片林间空地

他知道那里有一棵白桦树孤独站立,

顶着一只尖尖的叶子做的薄头巾,

长长的枝条像头发一样披在身后,

脖子上缠绕着一串串葡萄做的项链。

自从去年见过一次我就认得葡萄了。

开始是一嘟噜,然后是数不清的一串串

在白桦树的枝叶间若隐若现,

就像曾经在莱夫的周围若隐若现;

只可惜好多都长在我够不着的高处,

就像我小时候一心向往的月亮,要想

幸福地拥有它,就必须往上爬。

我哥哥爬了上去;一开始他摘些

葡萄,胡乱扔下来

害得我在香蕨木和绣线菊间找来找去;

这下他就有时间在树上放开吃,

但也许这对一个男孩来说不够爽,

于是他为了让我自个摘自个吃,

便又往高处爬,再将树枝踩压向地面

送进我手里,让我自己摘。

“赶紧抓住,我要去压另一根。

记住,我一走开你得牢牢抓住。”

我说我抓紧树枝了,其实不对。

应该反过来说,是树枝抓紧了我。

就在我哥哥离开的一刹那,树枝突然

把我高高钓起,就好像我是鱼,

树枝是鱼杆。这时我听见我哥哥

大喊大叫,声音都变了:“松手!

傻丫头!你连这都不会?松手!”

而我却像婴孩一样牢牢抓住树枝

这本能几乎在树上获得了遗传。

在远古时代,那些未开化的妈妈

曾让她们的孩子扯着双手吊在树上

不知道是为了锻炼还是晒太阳

(这你需要请教那些进化论专家)——

而我不敢对生命有任何抱怨。

我哥哥想把我逗笑,让我别紧张。

“你在那些葡萄中间干什么?

不用怕。几枝葡萄伤不了你。我是说,

如果你不摘它们,它们也不会摘你。”

这时我如果再摘真是不要命啦!

当时我几乎接受了这样一种哲学:

自己吊(活)也让别人吊(活)。

“这下你可尝到酸葡萄的滋味了,”

我哥哥继续说,“它们本以为长在树上

远离了贪吃的狐狸,而且长到了

出其不意的地方——桦树上,

狐狸根本想不到会长在那里——

即使看见了想去摘,也够不着——

可就在这时,咱俩来这儿摘葡萄了。

但是有一点证明你比那些葡萄强:

葡萄只是一根,你却有两只手

要想把你摘下来,确实更不易。”

帽子、鞋子,吧嗒吧嗒地掉下去,

我却依然吊在树上摇晃。我扬起脸

闭着眼睛不看太阳,耳朵

也不想听哥哥瞎胡说。“下来,”他说,

“我会接住你。这不是太高。”

(照他的身高来看是不太高。)

“下来吧,要不然我就把你摇下来。”

我没有吭声,尽管身体摇摇欲坠,

纤细的手指拉伸着,如同五弦琴。

“唉,你要是不这么死心眼就好了。

那就抓紧,让我想想别的招。

我再把树枝压弯到地上让你下来。”

当时是怎么下来的,我闹不明白;

只记得我穿长袜的脚一触到地面,

地球似乎在我脚下重新旋转起来,

我只顾看着我变得僵硬的手指头,

老半天才伸直,拍掉满手的树皮渣。

我哥哥对我说,“你有脑子没有?

下次遇到这种情况多长个心眼儿,

要不然,树枝又会把你吊到半空去。”

其实,那并不是因为我没有脑子,

就像我对这个世界并非一无所知——

虽然我哥哥从来比我懂得多。

当时我还不懂得急中生智学习知识;

还没有学会如何松手放弃,

就像直到现在我还不能多长个心眼儿,

总感觉没这兴趣,没这必要,

我能意识到这一点。是脑子,不是心眼。

我仍然需要活着,和任何人一样,

总想抛开那些让人头疼的问题——

这样就能个睡安稳觉;但是没什么

教导我必须多长个心眼儿。

Wild Grapes

WHATtree may not the fig be gathered from?

The grape may not be gathered from the birch?

It’s all you know the grape, or know the birch.

As a girl gathered from the birch myself

Equally with my weight in grapes, one autumn,

I ought to know what tree the grape is fruit of.

I was born, I suppose, like anyone,

And grew to be a little boyish girl

My brother could not always leave at home.

But that beginning was wiped out in fear 10

The day I swung suspended with the grapes,

And was come after like Eurydice

And brought down safely from the upper regions;

And the life I live now’s an extra life

I can waste as I please on whom I please.

So if you see me celebrate two birthdays,

And give myself out of two different ages,

One of them five years younger than I look—

One day my brother led me to a glade

Where a white birch he knew of stood alone,

Wearing a thin head-dress of pointed leaves,

And heavy on her heavy hair behind,

Against her neck, an ornament of grapes.

Grapes, I knew grapes from having seen them last year.

One bunch of them, and there began to be

Bunches all round me growing in white birches,

The way they grew round Leif the Lucky’s German;

Mostly as much beyond my lifted hands, though,

As the moon used to seem when I was younger,

And only freely to be had for climbing.

My brother did the climbing; and at first

Threw me down grapes to miss and scatter

And have to hunt for in sweet fern and hardhack;

Which gave him some time to himself to eat,

But not so much, perhaps, as a boy needed.

So then, to make me wholly self-supporting,

He climbed still higher and bent the tree to earth

And put it in my hands to pick my own grapes.

“Here, take a tree-top, I’ll get down another.

Hold on with all your might when I let go.”

I said I had the tree. It wasn’t true.

The opposite was true. The tree had me.

The minute it was left with me alone

It caught me up as if I were the fish

And it the fishpole. So I was translated

To loud cries from my brother of “Let go!

Don’t you know anything, you girl? Let go!”

But I, with something of the baby grip

Acquired ancestrally in just such trees

When wilder mothers than our wildest now

Hung babies out on branches by the hands

To dry or wash or tan, I don’t know which,

(You’ll have to ask an evolutionist)—

I held on uncomplainingly for life.

My brother tried to make me laugh to help me.

“What are you doing up there in those grapes?

Don’t be afraid. A few of them won’t hurt you.

I mean, they won’t pick you if you don’t them.”

Much danger of my picking anything!

By that time I was pretty well reduced

To a philosophy of hang-and-let-hang.

“Now you know how it feels,” my brother said,

“To be a bunch of fox-grapes, as they call them,

That when it thinks it has escaped the fox

By growing where it shouldn’t—on a birch,

Where a fox wouldn’t think to look for it—

And if he looked and found it, couldn’t reach it—

Just then come you and I to gather it.

Only you have the advantage of the grapes

In one way: you have one more stem to cling by,

And promise more resistance to the picker.”

One by one I lost off my hat and shoes,

And still I clung. I let my head fall back,

And shut my eyes against the sun, my ears

Against my brother’s nonsense; “Drop,” he said,

“I’ll catch you in my arms. It isn’t far.”

(Stated in lengths of him it might not be.)

“Drop or I’ll shake the tree and shake you down.”

Grim silence on my part as I sank lower,

My small wrists stretching till they showed the banjo strings.

“Why, if she isn’t serious about it!

Hold tight awhile till I think what to do.

I’ll bend the tree down and let you down by it.”

I don’t know much about the letting down;

But once I felt ground with my stocking feet

And the world came revolving back to me,

I know I looked long at my curled-up fingers,

Before I straightened them and brushed the bark off.

My brother said: “Don’t you weigh anything?

Try to weigh something next time, so you won’t

Be run off with by birch trees into space.”

It wasn’t my not weighing anything

So much as my not knowing anything—

My brother had been nearer right before.

I had not taken the first step in knowledge;

I had not learned to let go with the hands,

As still I have not learned to with the heart,

And have no wish to with the heart—nor need,

That I can see. The mind—is not the heart.

I may yet live, as I know others live, 100

To wish in vain to let go with the mind—

Of cares, at night, to sleep; but nothing tells me

That I need learn to let go with the heart.

□ 斧 把

还记得上回,有一根桤木枝忽然

从我身后抓住了我抡起的斧头。

不过那是在树林里,像是为了

阻止我去砍另一棵桤木的根,

毫无疑问,那就是根桤木枝。

但这次是个大活人,巴普迪斯特

一个雪天,他悄悄溜进我家院子

站在我身后,当时我正攥紧斧把

劈柴,不是在砍什么树。

刹时间我将斧头高高抡起,他

忽然从后面抓住斧头,稍停片刻

好让我回过神来,然后从我手里

拿了过去——我索性松手。

我跟他还不太熟悉,不知道他

这么干居心何在。他可能

有什么话要对我说,而且以为

对待坏邻居就该让他手无寸铁。

但是,他用法国味十足的英语

向我谈起的——不是我——只是

我的斧头;而我正担心

我手里的家伙有问题。事实是

我已买了人家的坏斧把——

“机器加工的,”他边说边用

厚厚的指甲在斧把的天然纹理上滑过,

手指像越过美圆上的两条线那样

飞快奔过人工拉制的蛇纹。

“只要磕到什么,斧把立马断。

斧头不知道会飞到哪儿去!”

言之有理,可这跟他有什么关系?

“上我家来,我给你换根

结实的斧把——绝对正宗的山桃木。

我亲手砍的!保证耐用!”

想在我这儿做买卖?可听起来不像。

“你说你什么时候来?

我分文不取。今晚怎样?”

今晚?那就今晚。

越过厨房里烧得旺旺的火炉,

我受到的欢迎和在别处毫无二致。

巴普迪斯特深知我为什么上门。

只要他不激动得讲出来,我就装作

不知道我来把他高兴成什么样儿,

(他或许真的高兴),他清楚

这下我就必须作出个判断,他那些

不为人知的关于斧头的知识

在邻居们眼里是不是一文不值。

这法国佬一心想融入我们新英格兰人,

难的是,他起码得有点儿本事!

巴普迪斯特太太进来坐在一把摇椅上

前后摇晃,那椅子像这个世界

一样在暗影中忽出忽进;

你几乎看不清她,因为她摇晃出

一连串的幻影,不知哪个是真。

她向前摇,差点跌进炉火的烈焰中,

幸亏她及时挺身,连人带椅子

猛然站了起来;然后退回去继续摇。

“她英语讲不大好——真糟糕。”

可我担心,巴普迪斯特太太向我

又向他丈夫微笑,似乎她明白

我们在讲什么,只是假装不懂。

巴普迪斯特也担心,但他更担心

他自己,因为,要是她那样摇下去,

他就别指望兑现今天早上和我

商量好的约定,好让我不去猜测

他这个人是不是言而无信。

巴普迪斯特兴冲冲地抱出他的斧把,

简直一大堆,因为,他希望

我能挑最好的,或者忍痛割爱——

不问我想要哪根,他拿出的这些

斧把,都有他能指出的好来,

任何一根都不能让我白白浪费。

他喜欢把斧把削得像鞭杆那么细,

上面全无节疤,能像在膝上

试长剑那样来回弯曲比划。

在动刀磨刮之前,他指给我看

一根好斧把到底会有怎样的纹理,

那不是人工拉制的,而是

自然而然,这种斧把才不怕

用力挥舞。他按住斧把从头到尾

来回打磨,直到变得亮光闪闪。

然后,他试着将它楔入斧孔中。

“嘿!嘿嘿!”他惊诧道,“刚刚好!”

巴普迪斯特知道怎样把短活儿拉长,

因为他爱干,但不是磨洋工。

你可知道,我们谈的是知识的问题?

巴普迪斯特竭力为不让孩子

或尽量不让孩子上学的事辩解——

说学校、孩子和我们对教育

的怀疑都和他那些斧把的天然纹理

有关,和他用心地磨刮它们有关,

并破例带我参观他的里屋。

难道,我这个人值得信任才受到邀请?

是不是,怀疑教育的人的正确与否

取决于这种人所受的教育?

但现在巴普迪斯特已拂净膝上的木屑,

将斧头头朝上把朝下竖了起来,

直直竖立,不是没有摇晃,就像

伊甸园里直起身子作恶的蛇——

头重脚轻,跟他又肥又短的手

一样笨拙,蓝幽幽的斧角

微微下倾——带一点法国风味。

巴普迪斯特仰身斜眯着眼睛打量斧头:

“你看它抬头挺胸嚣张得不行!”

The Ax-helve

I"ve known ere now an interfering branch

Of alder catch my lifted ax behind me.

But that was in the woods, to hold my hand

From striking at another alder"s roots,

And that was, as I say, an alder branch.

This was a man, Baptiste, who stole one day

Behind me on the snow in my own yard

Where I was working at the chopping block,

And cutting nothing not cut down already.

He caught my ax expertly on the rise,

When all my strength put forth was in his favor,

Held it a moment where it was, to calm me,

Then took it from me — and I let him take it.

I didn"t know him well enough to know

What it was all about. There might be something

He had in mind to say to a bad neighbor

He might prefer to say to him disarmed.

But all he had to tell me in French-English

Was what he thought of— not me, but my ax;

Me only as I took my ax to heart.

It was the bad ax-helve some one had sold me —

“Made on machine," he said, plowing the grain

With a thick thumbnail to show how it ran

Across the handle"s long-drawn serpentine,

Like the two strokes across a dollar sign.

“You give her "one good crack, she"s snap raght off.

Den where"s your hax-ead flying t"rough de hair?”

Admitted; and yet, what was that to him?

“Come on my house and I put you one in

What"s las" awhile — good hick"ry what"s grow crooked,

De second growt" I cut myself—tough, tough!”

Something to sell? That wasn"t how it sounded.

“Den when you say you come? It"s cost you nothing.

To-naght?”

As well to-night as any night.

Beyond an over-warmth of kitchen stove

My welcome differed from no other welcome.

Baptiste knew best why I was where I was.

So long as he would leave enough unsaid,

I shouldn"t mind his being overjoyed

(If overjoyed he was) at having got me

Where I must judge if what he knew about an ax

That not everybody else knew was to count

For nothing in the measure of a neighbor.

Hard if, though cast away for life with Yankees,

A Frenchman couldn"t get his human rating!

Mrs. Baptiste came in and rocked a chair

That had as many motions as the world:

One back and forward, in and out of shadow,

That got her nowhere; one more gradual,

Sideways, that would have run her on the stove

In time, had she not realized her danger

And caught herself up bodily, chair and all,

And set herself back where she ,started from.

“She ain"t spick too much Henglish— dat"s too bad.”

I was afraid, in brightening first on me,

Then on Baptiste, as if she understood

What passed between us, she was only reigning.

Baptiste was anxious for her; but no more

Than for himself, so placed he couldn"t hope

To keep his bargain of the morning with me

In time to keep me from suspecting him

Of really never having meant to keep it.

Needlessly soon he had his ax-helves out,

A quiverful to choose from, since he wished me

To have the best he had, or had to spare —

Not for me to ask which, when what he took

Had beauties he had to point me out at length

To ensure their not being wasted on me.

He liked to have it slender as a whipstock,

Free from the least knot, equal to the strain

Of bending like a sword across the knee.

He showed me that the lines of a good helve

Were native to the grain before the knife

Expressed them, and its curves were no false curves

Put on it from without. And there its strength lay

For the hard work. He chafed its long white body

From end to end with his rough hand shut round it.

He tried it at the eye-hold in the ax-head.

“Hahn, hahn,” he mused, “don"t need much taking down.”

Baptiste knew how to make a short job long

For love of it, and yet not waste time either.

Do you know, what we talked about was knowledge?

Baptiste on his defense about the children

He kept from school, or did his best to keep —

Whatever school and children and our doubts

Of laid-on education had to do

With the curves of his ax-helves and his having

Used these unscrupulously to bring me

To see for once the inside of his house.

Was I desired in friendship, partly as someone

To leave it to, whether the right to hold

Such doubts of education should depend

Upon the education of those who held them.

But now he brushed the shavings from his knee

And stood the ax there on its horse"s hoof,

Erect, but not without its waves, as when

The snake stood up for evil in the Garden—

Top-heavy with a heaviness his short,

Thick hand made light of, steel-blue chin drawn down

And in a little — a French touch in that.

Baptiste drew back and squinted at it, pleased:

“See how she"s cock her head!”

□西去的溪水

“佛瑞德,北在哪边?”

“北?那就是北,亲爱的。

溪水是向西流去的。”

“那我们就叫它西去的溪水吧,”

(直到今天人们还这样叫。)

“它干嘛要向西流去?

几乎所有国家的溪水都是向东流去。

这肯定是条背道而驰

且非常自信的溪水,如同

我相信你——你相信我——

因为我们是——我们是——我不知道我们是什么。

我们是什么?”

“人。年轻的或新的?”

“我们肯定是什么。

我说我们两个。让我们改说三个。

就像我和你结婚一样,

我们两个也将和溪水结婚。我们会在溪水上

架座桥并越过它,那桥就是

我们留下的手臂,在溪水边熟睡。

瞧,你瞧,它正用一个浪花冲我们招手呢

想让我们知道它听到了。”

“不会吧,亲爱的,

那浪花是在避开凸出的堤岸——”

(黑色的溪水撞在一块暗礁上,

回流时涌起一片洁白的浪花,

而且随波逐流不断翻涌着,

遮不住黑水也不消失,像一只鸟

胸前的白羽毛,

黑色的溪水和下游更黑的水

搏斗,激起白色的水沫

使得远处岸上的桤木丛好似一条白围巾。)

“我是说,自天底下有这溪水之日起

浪花就在避开凸出的堤岸

它并不是在冲我们招手。”

“你说不是,我说是。如果不是冲你

就是冲我——像在宣告什么。”

“哦,如果你把它带到女人国,

比如带到亚美逊人的国家

我们男人只能目送你到达边界

然后把你留在那儿,我们自己绝不能进去——

你的溪水就这样!我无话可说。”

“不,你有。继续说。你想到了什么。”

“说到背道而驰,你看这溪水

是怎样在白色的浪花中逆流而去。

它来自很久以前,在我们

随便成为什么东西之前的那水。

此时此刻,我们在自己焦躁的脚步声中,

正和它一起回到起点的起点,

回到奔流的万物之河。

有人说存在就像理想化的

普拉特或普拉特蒂,永远在一处

站立且翩翩起舞,但它流逝了,

它严肃而悲苦地流逝,

用空虚填满身不可测的空虚。

它在我们身边的这条溪水中流逝,

也在我们的头顶流逝。它在我们之间流逝

隔开我们在惊慌的一刻。

它在我们之中在我们之上和我们一起流逝。

它是时间、力量、声音、光明、生命和爱——

甚至流逝成非物质的物质;

这帘宇宙中的死亡大瀑布

激流成虚无——难以抗拒,

除非是藉由它自身的奇妙的抗拒来拯救,

不是突然转向一边,而是溯源回流,

仿佛遗憾在它心里且如此神圣。

它具有这种逆流而去的力量

所以这大瀑布落下时总会

举起点什么,托起点什么。

我们生命的跌落托起钟表的指针。

这条溪水的跌落托起我们的生命。

太阳的跌落托起这条溪水。

而且肯定有什么东西使太阳升起。

正由于这种逆流归源的力量,

我们大多数人才能在自己身上看到

那归源长河中涌流的贡品。

其实我们正是来自这个源头。

我们几乎都这样。”

“今天将是……你说这些的日子。”

“不,今天将是

你把溪水叫做西去的溪水的日子。”

“今天将是我们一起说这些的日子。”

译注:

1、 亚美逊人:又译亚马逊(孙)人,希腊神话中尚武善战的女性民族。

2、 普拉特或普拉特蒂:法国哑剧中两个理想化的人物。

West Running Brook

“Fred, where is north?”

“North? North is there, my love.

The brook runs west.”

“West-running Brook then call it.”

(West-Running Brook men call it to this day.)

“What does it think k"s doing running west

When all the other country brooks flow east

To reach the ocean? It must be the brook

Can trust itself to go by contraries

The way I can with you -- and you with me --

Because we"re -- we"re -- I don"t know what we are.

What are we?”

“Young or new?”

“We must be something.

We"ve said we two. Let"s change that to we three.

As you and I are married to each other,

We"ll both be married to the brook. We"ll build

Our bridge across it, and the bridge shall be

Our arm thrown over it asleep beside it.

Look, look, it"s waving to us with a wave

To let us know it hears me.”

“Why, my dear,

That wave"s been standing off this jut of shore –”

(The black stream, catching a sunken rock,

Flung backward on itself in one white wave,

And the white water rode the black forever,

Not gaining but not losing, like a bird

White feathers from the struggle of whose breast

Flecked the dark stream and flecked the darker pool

Below the point, and were at last driven wrinkled

In a white scarf against the far shore alders.)

“That wave"s been standing off this jut of shore

Ever since rivers, I was going to say,"

Were made in heaven. It wasn"t waved to us.”

“It wasn"t, yet it was. If not to you

It was to me -- in an annunciation.”

“Oh, if you take it off to lady-land,

As"t were the country of the Amazons

We men must see you to the confines of

And leave you there, ourselves forbid to enter,-

It is your brook! I have no more to say.”

“Yes, you have, too. Go on. You thought of something.”

“Speaking of contraries, see how the brook

In that white wave runs counter to itself.

It is from that in water we were from

Long, long before we were from any creature.

Here we, in our impatience of the steps,

Get back to the beginning of beginnings,

The stream of everything that runs away.

Some say existence like a Pirouot

And Pirouette, forever in one place,

Stands still and dances, but it runs away,

It seriously, sadly, runs away

To fill the abyss" void with emptiness.

It flows beside us in this water brook,

But it flows over us. It flows between us

To separate us for a panic moment.

It flows between us, over us, and with us.

And it is time, strength, tone, light, life and love-

And even substance lapsing unsubstantial;

The universal cataract of death

That spends to nothingness -- and unresisted,

Save by some strange resistance in itself,

Not just a swerving, but a throwing back,

As if regret were in it and were sacred.

It has this throwing backward on itself

So that the fall of most of it is always

Raising a little, sending up a little.

Our life runs down in sending up the clock.

The brook runs down in sending up our life.

The sun runs down in sending up the brook.

And there is something sending up the sun.

It is this backward motion toward the source,

Against the stream, that most we see ourselves in,

The tribute of the current to the source.

It is from this in nature we are from.

It is most us.”

“To-day will be the day....You said so.”

“No, to-day will be the day

You said the brook was called West-running Brook.”

“To-day will be the day of what we both said.”

□ 雪

三个人站立着,听狂风呼啸

片刻间,风卷着雪凶猛地撞击房子,

然后又鬼哭狼嚎。科尔夫妇

本已上床睡觉,衣服头发尽显凌乱,

莫瑟夫因裹着长毛大衣,看着更矮小。

莫瑟夫首先开腔。他将

手中的烟斗伸过肩头向外边戳了戳说:

“你简直能看清那阵风刮过屋顶

在半空中打开了一卷长长的花名册,

长得足以把我们所有人的名字写上去。——

我想,我现在得给家里打个电话,告诉她

我在这里——现在——等一会儿再出发。

就让铃轻轻响两声,要是她早睡了

但她够机灵,那就不必起来接听。”

他只摇了三下手柄,就拿起听筒。

“喂,丽莎,还没睡?我在科尔家。是晚了。

我只是想在回家对你说早上好

之前,在这儿对你说晚安——

会的——我知道,但是,丽莎——我知道——

会的,可那有什么关系?剩下的路

不会太糟——你再给我一个小时——哦,

三个小时就到这儿了!那全是上坡路;

其它都是下坡——哦,不,不会踢溜爬扑:

它们走得很稳,简直不慌不忙,跟玩儿

似的。它们这会儿都在棚里。——

亲爱的,我会回去的。我打电话

可不是让你请我回家——”

他似乎在等她不情愿地说出那两个字,

最终还是他自己说了:“晚安!”

那边没有应声,于是他挂断了电话。

三个人围着桌子,站在灯光下

低垂着眼睛,直到莫瑟夫又一次开口:

“我想去看看那些马咋样啦。”

“好,你去。”

科尔夫妇异口同声地。科尔太太

又补充道:“看过以后再决定——

佛瑞德,你在这儿陪我。让他留下。

莫瑟夫兄弟,你知道从这儿

去牲口棚的路。”

“我想我知道,

我知道在那里能看到我的大名

刻在牲口棚里,这样,即使我不知道

我身在何处,也知道我是谁。

我过去常这么玩——”

“你照看完它们就回来。——

佛瑞德·科尔,你怎么能让他走呢!”

“为什么不?那你呢?

你是不是要让他留下来?”

“我刚才叫他兄弟。

你知道我为什么那样叫他?”

“这不明摆着嘛。

因为你听周围的人都那样叫他。

他好像已失去了教名。”

“可我感觉那样叫有基督的味道。

他没注意到,是不是?那好,

至少,这并不表明我就喜欢他,

上帝知道。我一想到他有一大帮

不到十岁的孩子,就感觉很讨厌。

我也讨厌他那个芝麻大的邪恶教派,

据我所知,那个教派不怎么的。

但也难说——瞧,佛瑞德·科尔,

都十二点了,他在咱这儿已半小时了。

他说他九点离开镇上杂货店的。

三小时走四英里——一小时一英里

或者稍微多一点儿。这是怎的,

似乎一个男人不会走得这样慢。

想想看,这段时间他一定走得很吃力。

可他还有三英里路要走!”

“不要让他走。

留下他,海伦。让他陪你聊一聊。

那种人心直口快,说起来没完,

只要他自个谈起一件什么事,

别人说什么他都听不进,充耳不闻。

不过我想,你能让他听你说。”

“这样的夜晚他出来干什么?

他怎么就不能呆在家里呢?”

“他得布道。”

“这样的夜晚不该出门。”

“他也许卑微,也许

虔诚,但有一样你要相信:他很坚韧。”

“像一股浓浓的旱烟味儿。”

“他会坚持到底的。”

“说得轻巧。要知道从这儿

到他们家,不会再有别的过夜处。

我想,我该再给他妻子打个电话。”

“别急,他会打的。看他咋办。

咱看他会不会再想到他妻子。

但是我又怀疑,他只会想着他自己。

他不会把这种天气当回事。”

“他不能走——瞧!”

“那是夜,亲爱的。

至少他没把上帝扯进这件事。”

“他或许不认为上帝跟这有关。”

“你真这么想?你不了解这种人。

他这会儿一定想着创造一个奇迹呢。

悄悄的——就他晓得,这会儿,他肯定想

要是成功了,那就证明了一种关系,

失败的话就保持沉默。”

“永远保持沉默。

他会被冻死——被雪埋掉的。”

“言过其实!

不过,要是他真这样做,就会让那些

道貌岸然的家伙又表现出

假惺惺的虔诚。但我还是有一千个理由

不在乎他会出什么事。”

“胡言乱语!你希望他平平安安。”

“你喜欢这个小个子。”

“你不是也有点喜欢么?”

“这个嘛,

我不喜欢他做这种事,而这是

你喜欢的,所以你才喜欢他。”

“哦,肯定喜欢。

你像任何人一样喜欢有趣的事;

只有你们女人才会做出这种姿态

为给男人留下好印象。你让我们男人

感到害臊,即便我们看见

有趣的决斗也觉得有必要去制止。

我说,就让他冻掉耳朵吧——

他回来,我把他全交给你,

救他的命吧。——哦,进来,莫瑟夫。

坐,坐,你那些马怎样啦?”

“很好,很好。”

“还要继续走?我妻子

说你不能走。我看就算了吧。”

“给我个面子行不,莫瑟夫先生?

就当我求你。或者让你妻子决定好了。

她刚才在电话里说什么?”

除了桌上的灯和灯前的什么东西

莫瑟夫似乎再没注视什么。

他放在膝盖上的那只手活像一只

疙里疙瘩的白蜘蛛,他伸直

胳臂,举起食指指着灯下说:

“请看这些书页!在打开的书中!

我感觉它们刚才动了一下。它们一直

那样竖立在桌上,打我进来

它们就始终想向前或向后翻,

而我一直盯着想看出个结果;

要是向前,那它们就是怀着朋友的急躁——

你我心知肚明——要你继续看下去,

看你有什么感受;要是向后

那就是为着你翻过了却未能读到

精彩之处而感到遗憾。不要介意,

在我们理解事物之前,它们肯定会

一次次地向我们展现——我说不清

会重复多少次——那得看情况而定。

有一种谎言总企图证明:任何事物

只在我们面前显现一次。

如果真是那样,那我们最终会在哪里呢?

我们真实的生命依赖万物

的往复循环,直到我们在内心作出回应。

第一千次重现或许能证明其魅力——那书页!

它不能翻到任何一页,除非风帮忙。

但要是它刚才动了,却不是被风吹动。

它自己动的。因为这儿压根没有风。

风不可能让一件东西动得那样微妙。

风不可能吹进灯里让火焰喷出黑烟。

风不可能将牧羊犬的毛发吹得起皱。

你们使这块四平八稳的空间显得

安静、明亮而且温暖,尽管外面是

无边无际的黑暗、寒冷和暴风雨。

正是因为这样做,你们才让身边的

这三样东西——灯、狗和书页保持了自身的平静;

也许,所有人都会说,这平静

就是你们不可能拥有的东西,但你们却能给予。

所以,不拥有就不能给予是无稽之谈,

认为谎言重复千遍就成真理,也是错误。

我要翻一翻这书页,如果没人愿翻的话。

它不会倒下。那么就让它继续竖立。谁在乎呢?”

“我不是在催促你,莫瑟夫,

但要是你想走——哦,干脆留下。

让我拉开窗帘,你会看到

外面的雪有多大,不让你走。

你看见冰天雪地白茫茫一片对吧?

问问海伦,自打我们刚才看过以后

窗框上的雪又爬上去了多高!”

“那看上去像个

煞白煞白的家伙压扁了它的五官

并急急忙忙地合上了双眼,

不愿意瞧人们之间会发生

什么有趣的事,却由于愚蠢和不理解

而酣然入睡了,

或是折断了它白蘑菇般的

短脖子,紧贴着窗玻璃死掉啦。”

“莫瑟夫兄弟,当心,这神叨叨的话

只会吓住你自己,远远超过吓我们。

跟这有关系的是你,因为是你

要独自走出去,走进茫茫雪夜。”

“让他说,海伦,也许他会留下。”

“在你放下窗帘之前——我忽然想起:

你还记得那年冬天跑到这儿来

呼吸新鲜空气的那个小伙吧?——住在

艾弗瑞家的那个?对,暴风雪过后

一个晴朗的早晨,他路过我家

看见我正在屋外雪护墙。

为了取暖,我得把自己严严实实包围起来,

一直把雪堆到了窗台上。

堆到窗顶上的雪吸引了他的目光。

‘嘿!真有你的,’这就是他说的。

‘这样当你暖暖地坐在屋里,研究平衡分配,

就可以想像外面六英尺深的积雪,

在冬天你却感觉不到冬天。’

说完这些他就回家了。但是

在艾弗瑞的窗外,他用雪堵死了白昼。

现在,你们和我都不会做这种事了。

同时也不能否认,我们三个坐在这儿

发挥我们的想像力,让雪线攀升

高过外面的玻璃窗,这并不会使

天气变得更糟糕,一点也不。

在茫茫冰天雪地中,有一种隧道——

更像隧道而不像洞——你可以看见

隧道深处有一种搅动或震颤

如同破败的巷道边沿在风中

颤抖。那情形,我喜欢——真的。

好啦,现在我要离开你们上路了,朋友。”

“哦,莫瑟夫,

我们还以为你决定不走了呢——

你刚才还用那种方式说你在这儿

感觉自在呢。你其实想留下来。”

“必须承认,下这场雪够冷的。

而你们呆的这房间,这整幢房子

很快就会给冻裂。要是你们以为风声

远了,那不是因为它会消失;

雪下得越深——道理尽在其中——

你越感觉不到它。听那松软的雪炸弹

它们正在烟囱口上对着我们爆裂呢,

屋檐上也是。比起外面,我更喜欢

呆在房间里。但我的牲口都休息好了

而且也到说晚安的时候了,

你们上床歇息去吧。晚安,

抱歉我这不速之客,惊了你们的好梦。”

“你能来是你的运气。真的,

把我们家当作你中途的休息站。

如果你是那种尊重女人意见的人,

你就应该采纳我的建议

而且为你家人着想,留下不走。

但是,我这样苦口婆心又有什么用?

你所做的已经超过了你最大的

极限——如你刚才所说。你知道

继续走,这要冒多大的风险。”

“一般来说,我们

这里的暴风雪不会置人于死地。

虽说我宁可做一头藏在雪底下

冬眠的野兽,洞口被封死,甚至掩埋,

也不愿做一个在上面和雪搏斗的人。

你想想那栖息在枝头而不是安睡

在巢里的鸟吧。难道我还不如它们?

就在今晚,它们被雪打湿的身体

很快就会冻结成冰块。但是翌日清晨

它们又会回到醒来的树枝上跳跃,

扑闪着翅膀,叽叽喳喳欢唱,

仿佛不知道暴雨雪有什么意义。”

“可为什么呢,既然谁都不想让你再走?

你妻子——她不希望。我们也不,

你自己也不希望。其他还会有谁?”

“让我们不要被女人的问题难住。

哦,此外还有”—— 后来她告诉佛瑞德

在他停顿那会儿,她以为他会说

出“上帝”这个令人感到敬畏的字眼。

但他只是说“哦,此外还有——暴风雪。

它说我得继续走。它需要我如同

战斗需要我一样——如果真有战斗。

去问问随便哪个男人吧。”

他撂下最后一句话,让她

去傻不楞瞪,直到他走出门。

他让科尔陪他到牲口棚,送送他。

当科尔回来,发现妻子依然

站在桌边,靠近打开的书页,

但并不是在读它。

“好啦,”她说:

“你觉得他是个什么样的人?”

“应该说,他有

语言天赋,或者,能说会道?”

“这样的人从来就爱东拉西扯吗?”

“也许是漠视人们所问的世俗问题——

不,我们在一小时内对他的了解

比我们看他从这路上经过一千次

了解的还要多。他要这样布道才好呢!

毕竟,你不并没真想留住他。

哦,我不是在怪你。他总是

让你插不上嘴,但我很高兴,

我们不必陪他过一夜。他就是留下

也不会睡觉。芝麻大的事也会使他兴奋。

可他一走,咱这里静得像座空荡荡的教堂。”

“这比他没走又能好多少呢?

我们得一直坐这儿等,直到他安全到家。”

“是么,我猜你会等,但我不会。

他知道他的能耐,不然他不会走的。

我说,咱们上床吧,好歹休息一会儿。

他不会折回来的,既就是他来电话,

那也是在一两个小时以后。”

“那好。我想

我们坐在这儿陪他穿越暴风雪

也是白费油蜡。”

- - - - - - - - - - -

科尔一直在暗处打电话。

科尔太太的声音从里屋传来:

“她打过来的还是你打的?”

“她打的。

你要是不想睡就起来好了。

我们早该睡了:都三点多了。”

“她说了一会儿了?我去

把睡衣拿来。我想和她说说。”

“她只说,

他还没到家,问他是不是真走了。”

“她知道他走了,至少两个小时了。”

“他带着雪铲。他得铲雪开路。”

“天,为什么我刚才要让他离开呢!”

“别这样。你已尽力

留过他了——不过,你也许没

下老实挽留,你倒是希望他有勇气

违反你。他妻子会怪你的。”

“佛瑞德,我毕竟说过!不管怎样

你不能离了我的话而胡乱理解。

难道她刚才说的意思就是

要怪我?”

“我对她说‘走了,’

她说,‘好啊,’接着又‘好啊’——像在威胁。

然后声音低低地说:‘哦,你,

你们为什么要让他走呢?’”

“问我们为什么让他走?

你闪开!我倒要问问她为什么放他出来。

他在这儿的时候她咋不敢说呢。

他们的号码是——二○一?打不通。

有人把话筒撂下了。这摇柄太紧。

这破玩意儿,会扯断人的手臂!

通了!可她已撂下话筒走了。”

“试着说说。说‘喂!’”

“喂。喂。”

“听到什么了?”

“听到一个空房间——

真的——是空房间。真的,我听见——

有钟表声——窗户咔嗒响。

听不见脚步声。即便她在,也是坐着的。”

“大声点儿,她或许会听见。”

“大声也不顶用。”

“那就继续。”

“喂。喂。喂。

你想——她会不会是出门去了?”

“我担心,她可能真出去了。”

“丢下那些孩子?”

“等一会儿再喊吧。

你就听不出那门是不是敞开着

是不是风吹灭了灯,炉火也熄灭

房间里又黑又冷?”

“只有一种可能:她上床了,

要么就是出门了。”

“哪一种情况都不妙。

你知道她是怎样的人?你认识她?

真奇怪,她不想和我们说话。”

“佛瑞德,你来,看你能不能听见

我听见的那种声音。”

“感觉是钟表响。”

“就没听到别的?”

“不是说话声。”

“不是。”

“啊,我听见了——是什么呢?”

“什么?”

“一个婴儿的哭声!

听起来真凶,虽然感觉异常遥远。

当妈的不会让他那样哭的,

除非她不在。”

“这说明什么?”

“只有一种可能,

那就是——她出门去了。

不过,我想她没出去。”他们

就地坐下。“天亮以前我们毫无办法。”

“佛瑞德,我不允许你想到出去。”

“别出声。”电话突然响了。

他们站了起来。佛瑞德抓过话筒。

“喂,莫瑟夫。这么说你到了!——你妻子呢?

很好!我问这干吗——刚才她好像不接电话。

——他说刚才她去牲口棚接他了——

我们很高兴。哦,别客气,朋友。

欢迎你下次路过时再来看我们。”

“好了,

这下她终于得到他了,尽管我看不出

她为什么需要他。”

“她可能不是为她自己。

她需要他,也许只是为了那些孩子。”

“看来这完全是虚惊一场。

我们折腾这一夜难道只为让他觉得好笑?

他来干什么?——只是来聊聊?

不过他倒是打来电话告诉我们正在下雪。

要是他想把我们家变成往返城镇

中途休息的一个咖啡厅——”

“我想你刚才太过担心了。”

“难道刚才你就不担心?”

“如果你是说他不太为别人着想

半夜把我们从床上拉了起来,

然后又对我们的建议置之不理,

那我同意。但是,让我们原谅他。

我们已分享了他生命中的一个夜晚。

你敢不敢打赌,他还会再来的?”

Snow

THE THREE stood listening to a fresh access

Of wind that caught against the house a moment,

Gulped snow, and then blew free again—the Coles

Dressed, but dishevelled from some hours of sleep,

Meserve belittled in the great skin coat he wore.

Meserve was first to speak. He pointed backward

Over his shoulder with his pipe-stem, saying,

“You can just see it glancing off the roof

Making a great scroll upward toward the sky,

Long enough for recording all our names on.—

I think I’ll just call up my wife and tell her

I’m here—so far—and starting on again.

I’ll call her softly so that if she’s wise

And gone to sleep, she needn’t wake to answer.”

Three times he barely stirred the bell, then listened.

“Why, Lett, still up? Lett, I’m at Cole’s. I’m late.

I called you up to say Good-night from here

Before I went to say Good-morning there.—

I thought I would.— I know, but, Lett—I know—

I could, but what’s the sense? The rest won’t be

So bad.— Give me an hour for it.— Ho, ho,

Three hours to here! But that was all up hill;

The rest is down.— Why no, no, not a wallow:

They kept their heads and took their time to it

Like darlings, both of them. They’re in the barn.—

My dear, I’m coming just the same. I didn’t

Call you to ask you to invite me home.—”

He lingered for some word she wouldn’t say,

Said it at last himself, “Good-night,” and then,

Getting no answer, closed the telephone.

The three stood in the lamplight round the table

With lowered eyes a moment till he said,

“I’ll just see how the horses are.”

“Yes, do,”

Both the Coles said together. Mrs. Cole

Added: “You can judge better after seeing.—

I want you here with me, Fred. Leave him here,

Brother Meserve. You know to find your way

Out through the shed.”

“I guess I know my way,

I guess I know where I can find my name

Carved in the shed to tell me who I am

If it don’t tell me where I am. I used

To play—”

“You tend your horses and come back.

Fred Cole, you’re going to let him!”

“Well, aren’t you?

How can you help yourself?”

“I called him Brother.

Why did I call him that?”

“It’s right enough.

That’s all you ever heard him called round here.

He seems to have lost off his Christian name.”

“Christian enough I should call that myself.

He took no notice, did he? Well, at least

I didn’t use it out of love of him,

The dear knows. I detest the thought of him

With his ten children under ten years old.

I hate his wretched little Racker Sect,

All’s ever I heard of it, which isn’t much.

But that’s not saying—Look, Fred Cole, it’s twelve,

Isn’t it, now? He’s been here half an hour.

He says he left the village store at nine.

Three hours to do four miles—a mile an hour

Or not much better. Why, it doesn’t seem

As if a man could move that slow and move.

Try to think what he did with all that time.

And three miles more to go!”

“Don’t let him go.

Stick to him, Helen. Make him answer you.

That sort of man talks straight on all his life

From the last thing he said himself, stone deaf

To anything anyone else may say.

I should have thought, though, you could make him hear you.”

“What is he doing out a night like this?

Why can’t he stay at home?”

“He had to preach.”

“It’s no night to be out.”

“He may be small,

He may be good, but one thing’s sure, he’s tough.”

“And strong of stale tobacco.”

“He’ll pull through.’

“You only say so. Not another house

Or shelter to put into from this place

To theirs. I’m going to call his wife again.”

“Wait and he may. Let’s see what he will do.

Let’s see if he will think of her again.

But then I doubt he’s thinking of himself

He doesn’t look on it as anything.”

“He shan’t go—there!”

“It is a night, my dear.”

“One thing: he didn’t drag God into it.”

“He don’t consider it a case for God.”

“You think so, do you? You don’t know the kind.

He’s getting up a miracle this minute.

Privately—to himself, right now, he’s thinking

He’ll make a case of it if he succeeds,

But keep still if he fails.”

“Keep still all over.

He’ll be dead—dead and buried.”

“Such a trouble!

Not but I’ve every reason not to care

What happens to him if it only takes

Some of the sanctimonious conceit

Out of one of those pious scalawags.”

“Nonsense to that! You want to see him safe.”

“You like the runt.”

“Don’t you a little?”

“Well,

I don’t like what he’s doing, which is what

You like, and like him for.”

“Oh, yes you do.

You like your fun as well as anyone;

Only you women have to put these airs on

To impress men. You’ve got us so ashamed

Of being men we can’t look at a good fight

Between two boys and not feel bound to stop it.

Let the man freeze an ear or two, I say.—

He’s here. I leave him all to you. Go in

And save his life.— All right, come in, Meserve.

Sit down, sit down. How did you find the horses?”

“Fine, fine.”

“And ready for some more? My wife here

Says it won’t do. You’ve got to give it up.”

“Won’t you to please me? Please! If I say please?

Mr. Meserve, I’ll leave it to your wife.

What did your wife say on the telephone?”

Meserve seemed to heed nothing but the lamp

Or something not far from it on the table.

By straightening out and lifting a forefinger,

He pointed with his hand from where it lay

Like a white crumpled spider on his knee:

“That leaf there in your open book! It moved

Just then, I thought. It’s stood erect like that,

There on the table, ever since I came,

Trying to turn itself backward or forward,

I’ve had my eye on it to make out which;

If forward, then it’s with a friend’s impatience—

You see I know—to get you on to things

It wants to see how you will take, if backward

It’s from regret for something you have passed

And failed to see the good of. Never mind,

Things must expect to come in front of us

A many times—I don’t say just how many—

That varies with the things—before we see them.

One of the lies would make it out that nothing

Ever presents itself before us twice.

Where would we be at last if that were so?

Our very life depends on everything’s

Recurring till we answer from within.

The thousandth time may prove the charm.— That leaf!

It can’t turn either way. It needs the wind’s help.

But the wind didn’t move it if it moved.

It moved itself. The wind’s at naught in here.

It couldn’t stir so sensitively poised

A thing as that. It couldn’t reach the lamp

To get a puff of black smoke from the flame,

Or blow a rumple in the collie’s coat.

You make a little foursquare block of air,

Quiet and light and warm, in spite of all

The illimitable dark and cold and storm,

And by so doing give these three, lamp, dog,

And book-leaf, that keep near you, their repose;

Though for all anyone can tell, repose

May be the thing you haven’t, yet you give it.

So false it is that what we haven’t we can’t give;

So false, that what we always say is true.

I’ll have to turn the leaf if no one else will.

It won’t lie down. Then let it stand. Who cares?”

“I shouldn’t want to hurry you, Meserve,

But if you’re going— Say you’ll stay, you know?

But let me raise this curtain on a scene,

And show you how it’s piling up against you.

You see the snow-white through the white of frost?

Ask Helen how far up the sash it’s climbed

Since last we read the gage.”

“It looks as if

Some pallid thing had squashed its features flat

And its eyes shut with overeagerness

To see what people found so interesting

In one another, and had gone to sleep

Of its own stupid lack of understanding,

Or broken its white neck of mushroom stuff

Short off, and died against the window-pane.”

“Brother Meserve, take care, you’ll scare yourself

More than you will us with such nightmare talk.

It’s you it matters to, because it’s you

Who have to go out into it alone.”

“Let him talk, Helen, and perhaps he’ll stay.”

“Before you drop the curtain—I’m reminded:

You recollect the boy who came out here

To breathe the air one winter—had a room

Down at the Averys’? Well, one sunny morning

After a downy storm, he passed our place

And found me banking up the house with snow.

And I was burrowing in deep for warmth,

Piling it well above the window-sills.

The snow against the window caught his eye.

‘Hey, that’s a pretty thought’—those were his words.

‘So you can think it’s six feet deep outside,

While you sit warm and read up balanced rations.

You can’t get too much winter in the winter.’

Those were his words. And he went home and all

But banked the daylight out of Avery’s windows.

Now you and I would go to no such length.

At the same time you can’t deny it makes

It not a mite worse, sitting here, we three,

Playing our fancy, to have the snowline run

So high across the pane outside. There where

There is a sort of tunnel in the frost

More like a tunnel than a hole—way down

At the far end of it you see a stir

And quiver like the frayed edge of the drift

Blown in the wind. I like that—I like that.

Well, now I leave you, people.”

“Come, Meserve,

We thought you were deciding not to go—

The ways you found to say the praise of comfort

And being where you are. You want to stay.”

“I’ll own it’s cold for such a fall of snow.

This house is frozen brittle, all except

This room you sit in. If you think the wind

Sounds further off, it’s not because it’s dying;

You’re further under in the snow—that’s all—

And feel it less. Hear the soft bombs of dust

It bursts against us at the chimney mouth,

And at the eaves. I like it from inside

More than I shall out in it. But the horses

Are rested and it’s time to say good-night,

And let you get to bed again. Good-night,

Sorry I had to break in on your sleep.”

“Lucky for you you did. Lucky for you

You had us for a half-way station

To stop at. If you were the kind of man

Paid heed to women, you’d take my advice

And for your family’s sake stay where you are.

But what good is my saying it over and over?

You’ve done more than you had a right to think

You could do—now. You know the risk you take

In going on.”

“Our snow-storms as a rule

Aren’t looked on as man-killers, and although

I’d rather be the beast that sleeps the sleep

Under it all, his door sealed up and lost,

Than the man fighting it to keep above it,

Yet think of the small birds at roost and not

In nests. Shall I be counted less than they are?

Their bulk in water would be frozen rock

In no time out to-night. And yet to-morrow

They will come budding boughs from tree to tree

Flirting their wings and saying Chickadee,

As if not knowing what you meant by the word storm.”

“But why when no one wants you to go on?

Your wife—she doesn’t want you to. We don’t,

And you yourself don’t want to. Who else is there?”

“Save us from being cornered by a woman.

Well, there’s”—She told Fred afterward that in

The pause right there, she thought the dreaded word

Was coming, “God.” But no, he only said

“Well, there’s—the storm. That says I must go on.

That wants me as a war might if it came.

Ask any man.”

He threw her that as something

To last her till he got outside the door.

He had Cole with him to the barn to see him off.

When Cole returned he found his wife still standing

Beside the table near the open book,

Not reading it.

“Well, what kind of a man

Do you call that?” she said.

“He had the gift

Of words, or is it tongues, I ought to say?”

“Was ever such a man for seeing likeness?”

“Or disregarding people’s civil questions—

What? We’ve found out in one hour more about him

Than we had seeing him pass by in the road

A thousand times. If that’s the way he preaches!

You didn’t think you’d keep him after all.

Oh, I’m not blaming you. He didn’t leave you

Much say in the matter, and I’m just as glad

We’re not in for a night of him. No sleep

If he had stayed. The least thing set him going.

It’s quiet as an empty church without him.”

“But how much better off are we as it is?

We’ll have to sit here till we know he’s safe.”

“Yes, I suppose you’ll want to, but I shouldn’t.

He knows what he can do, or he wouldn’t try.

Get into bed I say, and get some rest.

He won’t come back, and if he telephones,

It won’t be for an hour or two.”

“Well then.

We can’t be any help by sitting here

And living his fight through with him, I suppose.”

- - - - - - - - - -

Cole had been telephoning in the dark.

Mrs. Cole’s voice came from an inner room:

“Did she call you or you call her?”

“She me.

You’d better dress: you won’t go back to bed.

We must have been asleep: it’s three and after.”

“Had she been ringing long? I’ll get my wrapper.

I want to speak to her.”

“All she said was,

He hadn’t come and had he really started.”

“She knew he had, poor thing, two hours ago.”

“He had the shovel. He’ll have made a fight.”

“Why did I ever let him leave this house!”

“Don’t begin that. You did the best you could

To keep him—though perhaps you didn’t quite

Conceal a wish to see him show the spunk

To disobey you. Much his wife’ll thank you.”

“Fred, after all I said! You shan’t make out

That it was any way but what it was.

Did she let on by any word she said

She didn’t thank me?”

“When I told her ‘Gone,’

‘Well then,’ she said, and ‘Well then’—like a threat.

And then her voice came scraping slow: ‘Oh, you,

Why did you let him go’?”

“Asked why we let him?

You let me there. I’ll ask her why she let him.

She didn’t dare to speak when he was here.

Their number’s—twenty-one? The thing won’t work.

Someone’s receiver’s down. The handle stumbles.

The stubborn thing, the way it jars your arm!

It’s theirs. She’s dropped it from her hand and gone.”

“Try speaking. Say ‘Hello’!”

“Hello. Hello.”

“What do you hear?”

“I hear an empty room—

You know—it sounds that way. And yes, I hear—

I think I hear a clock—and windows rattling.

No step though. If she’s there she’s sitting down.”

“Shout, she may hear you.”

“Shouting is no good.”

“Keep speaking then.”

“Hello. Hello. Hello.

You don’t suppose—? She wouldn’t go out doors?”

“I’m half afraid that’s just what she might do.”

“And leave the children?”

“Wait and call again.

You can’t hear whether she has left the door

Wide open and the wind’s blown out the lamp

And the fire’s died and the room’s dark and cold?”

“One of two things, either she’s gone to bed

Or gone out doors.”

“In which case both are lost.

Do you know what she’s like? Have you ever met her?

It’s strange she doesn’t want to speak to us.”

“Fred, see if you can hear what I hear. Come.”

“A clock maybe.”

“Don’t you hear something else?”

“Not talking.”

“No.”

“Why, yes, I hear—what is it?”

“What do you say it is?”

“A baby’s crying!

Frantic it sounds, though muffled and far off.”

“Its mother wouldn’t let it cry like that,

Not if she’s there.”

“What do you make of it?”

“There’s only one thing possible to make,

That is, assuming—that she has gone out.

Of course she hasn’t though.” They both sat down

Helpless. “There’s nothing we can do till morning.”

“Fred, I shan’t let you think of going out.”

“Hold on.” The double bell began to chirp.

They started up. Fred took the telephone.

“Hello, Meserve. You’re there, then!—And your wife?

Good! Why I asked—she didn’t seem to answer.

He says she went to let him in the barn.—

We’re glad. Oh, say no more about it, man.

Drop in and see us when you’re passing.”

“Well,

She has him then, though what she wants him for

I don’t see.”

“Possibly not for herself.

Maybe she only wants him for the children.”

“The whole to-do seems to have been for nothing.

What spoiled our night was to him just his fun.

What did he come in for?—To talk and visit?

Thought he’d just call to tell us it was snowing.

If he thinks he is going to make our house

A halfway coffee house ’twixt town and nowhere——”

“I thought you’d feel you’d been too much concerned.”

“You think you haven’t been concerned yourself.”

“If you mean he was inconsiderate

To rout us out to think for him at midnight

And then take our advice no more than nothing,

Why, I agree with you. But let’s forgive him.

We’ve had a share in one night of his life.

What’ll you bet he ever calls again?”

□ 星星分割器

“你知道猎户座总从天边升起。

先是一条腿迈过我们栅栏似的群山,

接着举起手臂,像是看我

借着灯火,在外面干我本该

在白天干完的农活。的确,

大地冻结之后,我只能干它结冻

之前我应该做的,阵风将几片

枯萎的落叶丢进我冒烟的

提灯,嘲笑我干活的熊样儿,

或者嘲笑猎户座让我走火入魔。

我倒要问问,一个人,难道

不该关心这冥冥中的影响力?”

布莱德·麦克劳林轻率地将

星星和他杂乱的农事混为一谈,

直到他不再做那无章的农活,

他一把火烧光了房子,骗取了火灾保险金

用得来的钱买了台天文望远镜

以满足他终身的好奇心——

关于我们在无限宇宙中所处的位置。

“你要那该死的东西干什么?”

我先前问他,“你不是有一个嘛!”

“别说它该死;只要不是

人类战争使用的武器,任何东西

都无可指责,”他当时说,

“如果我卖掉农场我就买一个。”

他那块地在耕作时总需要搬石头

而且里面有许多大石头搬不走,

所以农场很难转手;他折腾了很久

想卖农场卖不掉,只好

为得笔火灾保险干脆将房子全烧光

然后如前所说,如愿以偿。

有几个人早就听他这么说过:

“人世间最有趣的事就是目不转睛,

而让我们看得最远的就是

天文望远镜。我看每个镇

都该有热心人为他那里弄一台。

而在利特尔顿,非我莫属。”

如此大大咧咧信口开河,他烧毁房子

骗得保险金也就不足为奇。

但那天冷笑声在镇上四处弥漫

好让他知道我们不是孤陋寡闻,

等着吧——明天大家就会嘲笑他。

但第二天早上,我们首先

想的是一个人总会犯点儿错误,

如果我们搬着指头一个一个地数,

那么很快全都成了“独鬼子”。

要你来我往,就必须宽宏大量。

譬如那个经常偷东西的小偷,

我们没说不让他来教堂参加圣餐仪式,

只是丢的东西他得还回来,

只要没吃掉,没弄坏,没转手。

所以不能因为一台天文望远镜

就对布莱德说三道四。毕竟他一把年纪

不可能得到这样一份圣诞礼物,

他只能用自以为是的办法

给自己弄一个。好,我们只说

他还以为这事能把我们蒙在鼓里呢。

居然有人为那房子唉声叹气,

那是一幢年代久远的原木房子,

但房子没有感觉,房子不会

知道任何事。即便它有,那

为什么不把它看成是某种祭品呢,

一种过时的火中的祭品,

而不是新式的亏本拍卖的商品?

一根火柴哧啦一声划掉了房子

也划掉了整个农场,布莱德不得不

改行到康科德铁路公司谋生,

在一个车站上做车票代理,

当他不卖票的时候,他就

满怀热情地忙活,当然这不像

在农场上那样,而是观望各种星星

红色绿色五颜六色。

他花600美元买了台很棒的望远镜。

新工作使他有闲暇观望星星。

他经常邀请我去一道观望

透过衬着黑天鹅绒的黄铜色圆镜筒,

看另一端瑟瑟发抖的星星。

我记得那是一个云彩细碎的夜晚

脚下的积雪早已融化成冰,

更在寒风中冻结成泥泞。

布莱德和我一起搬出那台望远镜:

叉开它的三脚支架,叉开我们的双腿。

我们的心思对准它对准的方位,

在闲暇中站立等待黎明到来,

聊起了一些从来没有聊过的好事情。

那台望远镜美其名曰“星星分割器”,

因为它只能将星星一分为二

或一分为三,就像你用一根手指

逢中一击,将掌心的一滴水银分割成

两三滴,其他再没别的功能。

如果真有星星分割器那这就是一个代表

如果分割星星和用斧头劈柴

一样有趣,那它还算是用点用。

我们看啊看,眼睛睁得像鸡蛋,可我们

看见了什么?我们究竟在哪里?

而在今晚,这个东西又是怎样架在夜空

和有着一个冒烟的提灯的人之间?

那叉开腿的架势难不成会有更大的变化?

Star-Splitter, The

“You know Orien always comes up sideways.

Throwing a leg up over our fence of mountains,

And rising on his hands, he looks in on me

Busy outdoors by lantern-light with something

I should have done by daylight, and indeed,

After the ground is frozen, I should have done

Before it froze, and a gust flings a handful

Of waste leaves at my smoky lantern chimney

To make fun of my way of doing things,

Or else fun of Orion"s having caught me.

Has a man, I should like to ask, no rights

These forces are obliged to pay respect to?”

So Brad McLaughlin mingled reckless talk

Of heavenly stars with hugger-mugger farming,

Till having failed at hugger-mugger farming,

He burned his house down for the fire insurance

And spent the proceeds on a telescope

To satisfy a life-long curiosity

About our place among the infinities.

“What do you want with one of those blame things?”

I asked him well beforehand. “Don"t you get one!”

“Don"t call it blamed; there isn"t anything

More blameless in the sense of being less

A weapon in our human fight," he said.

"I"ll have one if I sell my farm to buy it.”

There where he moved the rocks to plow the ground

And plowed between the rocks he couldn"t move,

Few farms changed hands; so rather than spend years

Trying to sell his farm and then not selling,

He burned his house down for the fire insurance

And bought the telescope with what it came to.

He had been heard to say by several:

“The best thing that we"re put here for"s to see;

The strongest thing that"s given us to see with"s

A telescope. Someone in every town

Seems to me owes it to the town to keep one.

In Littleton it may as well be me.”

After such loose talk it was no surprise

When he did what he did and burned his house down.

Mean laughter went about the town that day

To let him know we weren"t the least imposed on,

And he could wait--we"d see to him to-morrow.

But the first thing next morning we reflected

If one by one we counted people out

For the least sin, it wouldn"t take us long

To get so we had no one left to live with.

For to be social is to be forgiving.

Our thief, the one who does our stealing from us,

We don"t cut off from coming to church suppers,

But what we miss we go to him and ask for.

He promptly gives it back, that is if still

Uneaten, unworn out, or undisposed of.

It wouldn"t do to be too hard on Brad

About his telescope. Beyond the age

Of being given one"s gift for Christmas,

He had to take the best way he knew how

To find himself in one. Well, all we said was

He took a strange thing to be roguish over.

Some sympathy was wasted on the house,

A good old-timer dating back along;

But a house isn"t sentient; the house

Didn"t feel anything. And if it did,

Why not regard it as a sacrifice,

And an old-fashioned sacrifice by fire,

Instead of a new-fashioned one at auction?

Out of a house and so out of a farm

At one stroke (of a match), Brad had to turn

To earn a living on the Concord railroad,

As under-ticket-agent at a station

Where his job, when he wasn"t selling tickets,

Was setting out up track and down, not plants

As on a farm, but planets, evening stars

That varied in their hue from red to green.

He got a good glass for six hundred dollars.

His new job gave him leisure for star-gazing.

Often he bid me come and have a look

Up the brass barrel, velvet black inside,

At a star quaking in the other end.

I recollect a night of broken clouds

And underfoot snow melted down to ice,

And melting further in the wind to mud.

Bradford and I had out the telescope.

We spread our two legs as it spread its three,

Pointed our thoughts the way we pointed it,

And standing at our leisure till the day broke,

Said some of the best things we ever said.

That telescope was christened the Star-splitter,

Because it didn"t do a thing but split

A star in two or three the way you split

A globule of quicksilver in your hand

With one stroke of your finger in the middle.

It"s a star-splitter if there ever was one

And ought to do some good if splitting stars

"Sa thing to be compared with splitting wood.

We"ve looked and looked, but after all where are we?

Do we know any better where we are,

And how it stands between the night to-night

And a man with a smoky lantern chimney?

How different from the way it ever stood?

川公网安备 51041102000034号

川公网安备 51041102000034号