∞文章来源:The Airship

豪尔赫·路易斯·博尔赫斯,享誉世界的晚年失明的阿根廷作家、短篇小说大师,他的小说里充满了迷宫和镜子等意象,在20世纪60年代,他声名远播,从拉丁美洲走向了全世界。他与塞缪尔·贝克特分享了1961年的福门托国际奖,同时也为他迎来了最初的关注。1962年,他两部重要作品集和短篇作品的英文译本《杜撰集》和《迷宫》出版,给他带来了更多的读者。20世纪60年代至70年代“拉美文学爆炸”期间的拉美作家,以及马尔克斯《百年孤独》的成功,也让人们对博尔赫斯的作品增加了兴趣。

在拉丁美洲以外,博尔赫斯仍是以他的小说著名,而在拉丁美洲,人们有时候会说,他的非虚构散文才是他最有力的作品。如果博尔赫斯的小说一共是1000页,那么它的非虚构类作品数量要达到好几倍。他写影评、书评,序言、社论以及表达哲学观点的散文,也包括现代作家的传记。他还发表了上百篇关于探戈、民间传说、文学、国家政治等阿根廷文学和文化主题的文章。

正是在他的非虚构随笔集里,博尔赫斯阐述了那些推动了他短篇小说情节的想法。正是在他的非虚构随笔集里,博尔赫斯对《一千零一夜》的多个不同译本进行了评论,写下了《持久的地狱》和一篇《天使的历史》(A History of Angels,1926)。正是在他的非虚构随笔集里,博尔赫斯嘲笑种族主义和民族主义,并在阿根廷上层阶级日益同情法西斯主义时期强烈地反对反犹主义和纳粹。在这种背景下,博尔赫斯写这样文章的危险性很快给他带来了结果:由于博尔赫斯支持反庇隆的阿根廷作家协会,庇隆和他的政府将博尔赫斯从他的政府职位——米格尔·卡内图书馆(Miguel Cané Library)馆员“提拔”成科尔多瓦国营市场的家禽及家兔稽查员,实际上是强迫他辞去政府服务岗位。

他最早的非虚构类随笔开始于20世纪20年代,近乎天书。博尔赫斯自己也否定了它们,试图买回他早期这三本书在市场上的所有复本,并拒绝在他的有生之年让它们重新出版,只有一本法语译本的文集除外。它们的重要性在于,暗含了博尔赫斯在他此后的作家生涯里深入阐述的主题。20世纪30年代,博尔赫斯开始简化并润色他的文字风格,同时经常在报纸杂志上发表文章。他花了三年时间(1936-1939译注)为一本妇女双周刊《家庭》(El Hogar)写作。

博尔赫斯非虚构作品的创作最重要的时期开始于1932年《讨论集》的出版,一直持续到1956年他完全失明,期间有丰富的散文、序言和书评、电影评论写就。失明之后,博尔赫斯大多写诗,因为诗歌可以在他的头脑中构思,但他也继续写了许多书的序言并接受采访,也在他可以自然讨论的主题上做讲座,这些演讲随后也被记录下来,成为他非虚构作品的一部分。

博尔赫斯在他的非虚构作品中不仅展现了他强大的、众所周知的博学多识,也有他的幽默。在《的译者们》中,他写道,“现在看来很浅薄的东方学曾经使众多吸鼻烟的人目瞪口呆,并且使他们造成了一场五幕悲剧。(引自王永年译本原文《永恒史》上海译文出版社,2015)”在对电影《扬帆》(Now,Voyager,1942)的评论中,他把贝蒂·戴维斯(Bette Davis饰演女主角)描写成“被一副墨镜和一个专横的母亲拖累”的人。

他甚至经常地表现出在一两行文字之内挖苦别人的能力。他对电影《人与兽》(《化身博士》Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,1941)的评论(引自徐鹤林译本原文《讨论集》上海译文出版社,2015)这样开始:

好莱坞已经是第三次败坏罗伯特·罗伊斯·斯蒂文森的名声了。这一次遭殃的是《人与兽》,是维克多·弗莱明(Victor Fleming)干的,他不幸忠实于玛莫利安版本(反常版本)的美学道义和错误。

博尔赫斯评价,在T.S.艾略特的早期诗歌和散文中(引自黄锦炎译文原文《文稿拾零》上海译文出版社,2017),

拉弗格(现代自由诗的开创者之一)对他的影响是明显的,有时是致命的。

关于阿尔弗雷德·希区柯克的《阴谋破坏》(Sabotage,1936),博尔赫斯写道(Two Films,1943):

熟练的摄影,笨拙的制片——这就是我被希区柯克的最新电影激发出来的冷漠的观点。

有兴趣阅读以上作品的全部内容?由爱略特编辑、企鹅图书出版的《非虚构作品选集》是一个不错的开始。

Borges, Master of Nonfiction

by Tom Griggs

Jorge Luis Borges, the blind Argentine writer known internationally as the master of miniaturist short stories filled with labyrinths and mirrors, rose to prominence outside of Latin America during the 1960s. He split the 1961 Prix International with Samuel Beckett, bringing him initial attention. In 1962, English translations of two of his major collections of short stories appeared, Ficciones and Labyrinths, bringing him even wider readership. The “Latin American Boom” of Latino writers in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the success of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude brought still further interest to Borges’s work.

While Borges remains best known outside of Latin America for his fiction, inside Latin America, it is sometimes said his nonfiction essays are his strongest works. If Borges’s fiction totals 1,000 pages, his nonfiction totals that several times over. He wrote film and book reviews, book prologues, essays on social events and philosophical ideas, as well as biographies of modern writers. He also published hundreds of articles on Argentine literature and culture — the tango, folklore, literature, national politics.

It is here in his nonfiction essays that Borges elaborates on the ideas that propel his short stories. It is here that he critiqued the various translations of The Thousand and One Nights, pondered the duration of Hell and wrote a history of angels. It is also here that Borges ridiculed racism and nationalism and took aggressive stands against anti-Semitism and the Nazis in an era of rising sympathy for fascists among the upper-classes in Argentina. The risks inherent in writing these articles in that milieu can be seen in the consequences: Borges’s support of the Allies lead Argentine President Juan Perón and his administration to “promote” Borges from his government position at the Miguel Cané Library to official Inspector of Poultry and Rabbits in the Córdoba municipal market, in effect forcing him to resign from government service.

His earliest nonfiction essays from the 1920s are close to impenetrable, and Borges himself disowned them, attempting to buy up all copies of the three original books that compiled the work from this early era and refusing to let them be republished during his lifetime except for selections in a French translation. Their importance is in suggesting the themes that Borges would develop during the rest of his career. In the 1930s, Borges began to simplify and polish his style, and also to publish regularly in newspapers and magazines. Borges spent three years as a writer for El Hogar, a woman’s journal, publishing a piece every two weeks.

Borges’s most important period of nonfiction writing begins in 1932 with the publication of Discusión and ends in 1956 with the arrival of his complete blindness, a fertile period of essays, book prologues, as well as book and movie reviews. After his blindness, Borges mostly wrote poetry because he could compose it in his head, but he also continued to write numerous book prologues and to give interviews and lectures in which he would talk spontaneously on subjects that would later be written down and included as part of his nonfiction work.

In his nonfiction, Borges shows not only his overwhelming and well-known erudition, but also his humor. In “The Translators of The Thousand and One Nights” he writes, “Orientalism, which seems frugal to us now, was bedazzling to men who took snuff and composed tragedies in five acts.” In a review of the movieNow Voyager, he describes Bette Davis as “weighed down by a pair of sunglasses and a domineering mother.”

He even more frequently exhibits his ability to obliterate others in an almost offhanded line or two. His starts his review of the film The Man and the Beast by writing, “Hollywood has defamed, for the third time, Robert Louis Stevenson. In Argentina the title of this defamation isEl hombre y la bestia[The Man and the Beast] and it has been perpetrated by Victor Flemming, who repeats with ill-fated fidelity the aesthetic and moral errors of Mamoulian’s version — or perversion.” Borges remarks that in T.S. Eliot’s early poems and essays, “The influence of Laforgue is apparent, and sometimes fatal.” On Alfred Hitchcock’s Sabotage Borges writes, “Skillful photography, clumsy filmmaking — these are my indifferent opinions ‘inspired’ by Hitchcock’s latest film.”

Interested in reading these works in their entirety? Selected Non-Fictions edited by Eliot Weinberger and published by Penguin Books is a great place to start.

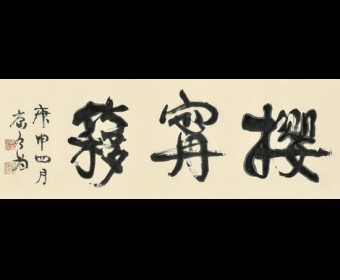

图片:博尔赫斯人形立牌

by Ariel Grinberg

川公网安备 51041102000034号

川公网安备 51041102000034号